The Library: An Arena for the Construction of Knowledge

The classification systems that we use to organise libraries shape the meaning, accessibility and perceived legitimacy of the knowledge constrained within them. They operate through inclusion and exclusion, defining what knowledge is central and what is peripheral. They determine who’s voices are heard and in what context. For example, a book about Palestinian fighters takes on a very different meaning when categorised under Terrorism vs. when it is categorised under Revolutionary Movements.

Libraries, then, are arenas for the construction of knowledge, truth and reality.

However, you as a reader have no voice in how these systems portray reality. Instead, they directly reflect the biases of the society that create them and are famously resistant to change. It is therefore alarming that the world’s most popular library classification system, the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC), was invented in the US in 1876 and has since completely failed to adapt to contemporary knowledge practices.

The DDC perpetuates outdated views and hierarchies, marginalises voices and perspectives that deviate from the norm and reinforces archaic power structures. This is evident in how the DDC disproportionately allocates space to Christian texts, or how how certain texts related to homosexuality are still filed under 616.8583 (sexual practices viewed as medical disorders). In fact, marginalised groups such as women, ethnic minorities, LGBTQ+ individuals, and people with disabilities are all structurally disenfranchised within today’s libraries. Essentially, any text that deviates from the Eurocentric, male, heterosexual norms underlying library classifications, is at a disadvantage.

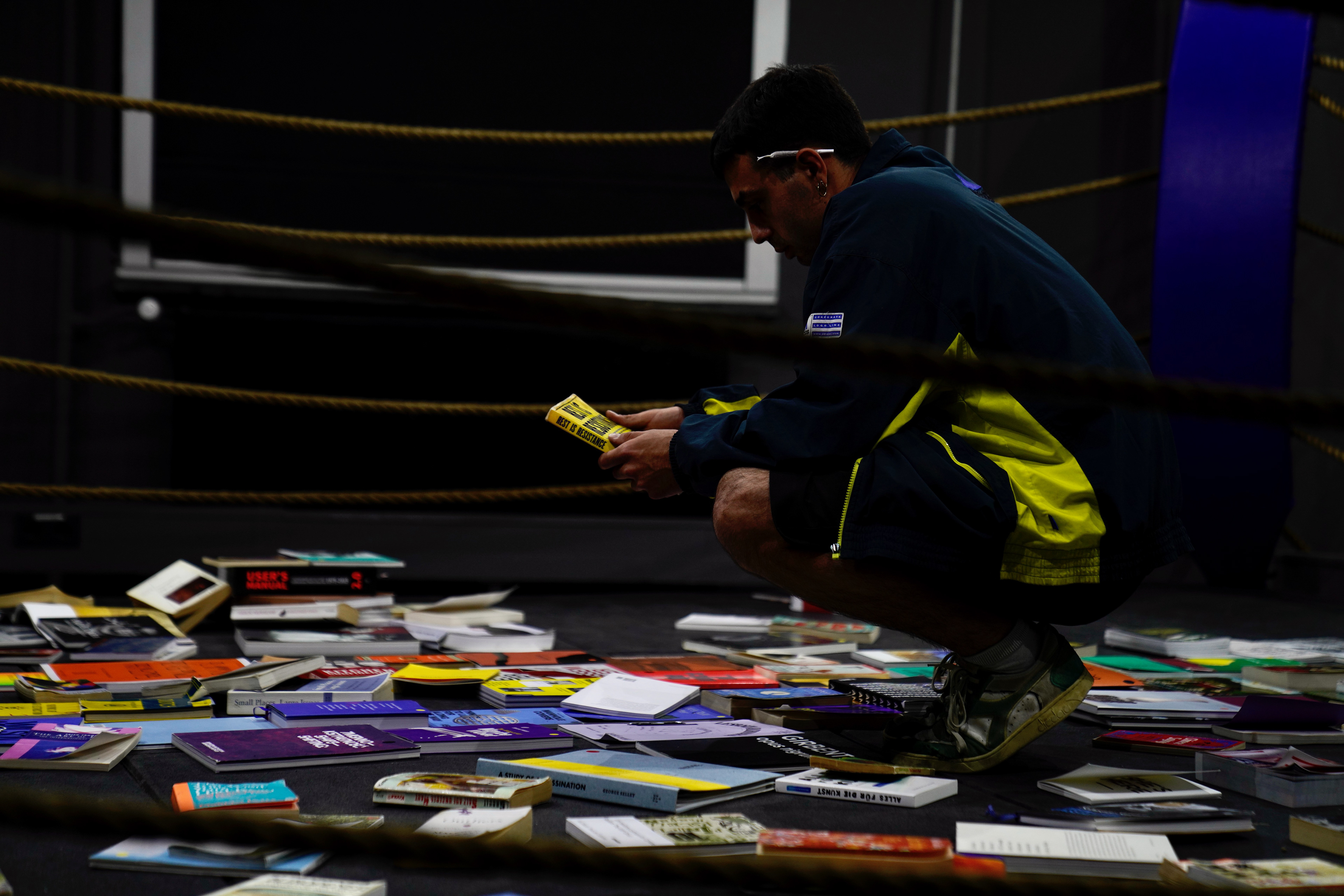

To address these issues, we must rethink our approach to library classification. Rather than refining existing categories (and thereby sharpening a tool of oppression), we need to create dynamic, user-driven knowledge environments that challenge traditional hierarchies and allow for serendipitous interactions between readers and texts. Imagine a library where books are not constrained by fixed categories but continuously reordered by users, reflecting evolving cultural discourses and fostering unexpected connections. Neither books nor the reader’s curiosity must submit to a set of rules in this space.

So this is what I ask of you: Step into the ring. Let a book catch your eye. Pick it up or sit down with it. Where do you feel it belongs? How do the books around it change its meaning? If you like, reposition it. Check back later to see if it has moved.

By tracking the positions of books with an overhead camera and a custom object detection algorithm, this library will, over time, reveal readers’ connections between different texts, thereby hinting at a publicly negotiated emergent order.

Stepping into the Ring

Situating the dynamic library within a boxing ring acknowledges that classification systems are nearly always a site of violence. It appropriates a hyper masculine environment to uncover the patriarchal structures that underly our knowledge practices, offering an almost ironic look at these. We are reminded that, whilst we may be challenging the logics underlying systems of classification, we are doing this within, and as subjects of a patriarchal system.

The close quarters of a boxing ring force encounters between different books and their readers. Inviting you to step into a ring and take an active role in knowledge organisation acknowledges that this negotiation of order will be no clean or easy fight. The library should be a space for disciplines, ideas and ways of knowing to clash, challenging each other’s methods, assumptions, and conclusions.

Whichever face-off you read into it, a boxing ring as the setting for this dynamic library emphasises the active, engaged, and often confrontational nature of learning, intellectual exploration and the construction of knowledge. It challenges the tradition of libraries as quiet, passive and even oppressive environments and reimagines them as active, dynamic arenas for intellectual engagement worthy of public attention and excitement.

I firmly believe that user-driven libraries could be a new public forum for ideas, dialogue and demonstration. That they might change our behaviour in libraries from knowledge retrieval to knowledge production by allowing for interactions between different texts (and their readers) that would be impossible in rigidly classified environments.

This is what I hope to achieve with this project, in graduation and thereafter: To dramatise intersectionality through intertextuality and reader relations by highlighting classification systems as power-knowledge technologies and inviting readers to break their shackles.

My hope is also that you begin to sense the power and responsibility the job of library organisation entails and why we should reclaim it.

Thank you for your time,

Lorenz Beckmann

P.S. I’d like to use this last bit of my paper and your attention span to thank Cristina Cochior, Cleo Foole, Boris Smeenk, Mitchell Kester, Raymond Molendijk, Ife Carter and Idea Books NL for their guidance and support in this project.